Each spring, many birders and naturalists travel to western Kansas and hunker in the grass for hours until dawn, at which point they are rewarded with a truly show-stopping performance. They are here to see Lesser Prairie Chickens, the charismatic Great Plains birds famous for their elaborate courtship dances. These iconic birds are threatened by habitat loss from agriculture and development, so in order to help conserve them, researchers are trying to learn more about how these birds use grasslands to thrive and reproduce.

Male (left) and female (right) Lesser Prairie-Chickens (Wikimedia Commons).

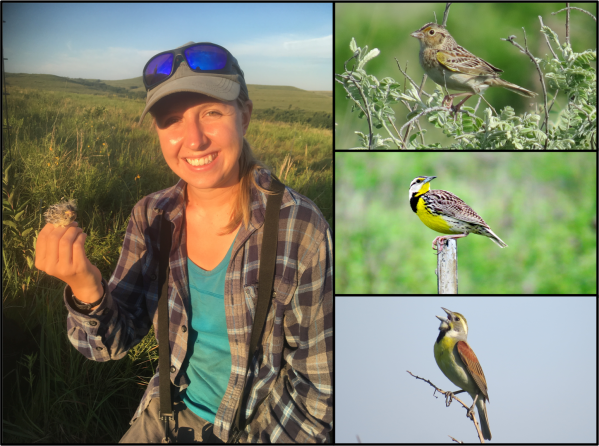

These mating rituals are a key research focus for those studying Lesser Prairie Chickens. During breeding season, all the males gather together in one spot and try to dance their way into the hearts of some lovely hens; this phenomenon is called a lek. “Lek” is a funny word that refers both to the behavior and to the physical place where the birds gather. Right now, it’s poorly understood what factors drive where a lek pops up on a landscape. This is a critical knowledge gap, and insight into the birds’ reproductive habitat requirements will help landowners and conservationists to protect and restore their habitat. Carly Aulicky, a Ph.D. candidate working with Dr. David Haukos in the Kansas State University Division of Biology, is getting to the bottom of where these leks form and why they form where they do. Carly led a discussion related to her research with Lesser Prairie Chickens at the Science on Tap event on January 23.

Differences in male and female reproductive roles may drive where leks occur. Male and female Lesser Prairie Chickens have vastly different roles in reproduction, so they use the landscape quite differently. Males want to attract a mate and be seen: during the breeding season, they are easily distinguished by their brightly colored eyebrows, inflated air sacs, and ostentatious neck feathers. They also like to be standing in short grass so they can be seen far and wide. Females, however, leave the lek and prepare to become solo parents. Unlike the males, they spend most of their time in tall grass that will hide their chicks from predators. These two facts lead to the hotspot hypothesis: certain spots on a landscape provide both short and tall grass to meet both the male and female birds’ needs, and these places are most likely to support a lek.

Carly’s work looks to test this hypothesis, and to do so she must track where Lesser Prairie Chickens go. Because the female hens blend into the tall grasslands and are seldom seen, Carly’s team has developed an ingenious solution to track these elusive birds: GPS. Each female bird is outfitted with a backpack-like tracker that transmits the bird’s location several times per day. These females can wander more than 500 km2 during a season, and these backpacks can map their movements for their entire lifespan. Carly and her team integrate these detailed movements with land use cover maps (see inset) from the landowners they work with, and they assess whether female movements on the landscape drive where males establish their lek.

So far, Carly’s data support the hotspot hypothesis: leks usually form on the edge of fields with different management regimes, such as a boundary between an ungrazed (taller grass) and heavily grazed (shorter grass) prairie. These results make it easier to anticipate where future leks may pop up, and it gives Carly’s lab a chance to work with landowners to restore and protect prime lek habitat. Kansans love these birds, but Carly’s research suggests that they need specialized habitat requirements to mate successfully and thrive as a species. Her work in the Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit allows her to collaborate with private landowners and support the persistence of these iconic Great Plains birds.

In addition to Carly’s work on where leks form, her research also explores what factors control how long these leks persist, the traits of the birds that visit leks, and how prairie chickens operate socially.

For more information on Carly’s work, visit her website (https://caulicky.com) or follow her on Twitter (@CarlyAulicky). To see a short video about Lesser Prairie Chickens, visit https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dTX5CD41zy0. To hear more about science research happening in your community, attend the Science on Tap series, run by the Sunset Zoo and Tallgrass Taphouse.

Caitlin is a Ph.D. student in the Division of Biology studying the effects of climate manipulations on tallgrass prairie ecosystem processes.